Auschwitz ~ Bearing Witness

From 1st - 5th November 2021, I spent my days in Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II - Birkenau together with a group of 33 other international peace activists and spiritual leaders for the Zen Peacemakers International Bearing Witness Retreat.

We started our days with deep sharing of our processes, thoughts, experiences and feelings in small council groups, before slowly making our way to the concentration camp - either by bus or by foot.

During the first days, we were guided around the camp by a museum guide and given a good introduction into the horrors and history of this place.

Once we had landed and located ourselves in the context, we then spent much of the remaining time sitting in meditation at the landing and selection platform - the place where Jewish prisoners stepped off the trains to either be sent to immediate death in the gas chambers, or to be selected for arduous work in the camp.

We also performed different sacred rituals of Buddhist, Christian and Jewish traditions, as well as other offerings of healing, blessing and humanness in the barracks, in the sauna, by the ruins of gas chambers and crematoria, along the paths prisoners and death-sentenced souls had to march, or by the memorials.

How to put words to this experience?

Since I returned almost a week ago, I have felt a deep silence, a deep wordlessness in me.

How to put words to this experience?

How to put into words the indescribable?

The many stories of the millions of souls, just tiny glimpses, little fragments of once rich and vibrant lives - now mere reverberations of unspeakable horrors and atrocities.

Taken out of our sacred retreat container, the experience seems incomprehensible, inexplicable, almost unreal.

How can you bear witness to so much violence, cruelty, suffering, abuse of power?

How they tried to destroy the evidence of what they did, breaking down barracks, destroying gas chambers and crematoria, trying to dismantle and hide their crimes as if no one would notice the stench of burning flesh, or the missing of 1.5 million people.

How the apparently so pretty and peaceful ponds are filled with the ashes and broken lives of hundreds of thousands.

How there was not a single blade of grass or single leaf on a tree left back then, all was eaten by hungry skeletal ghosts.

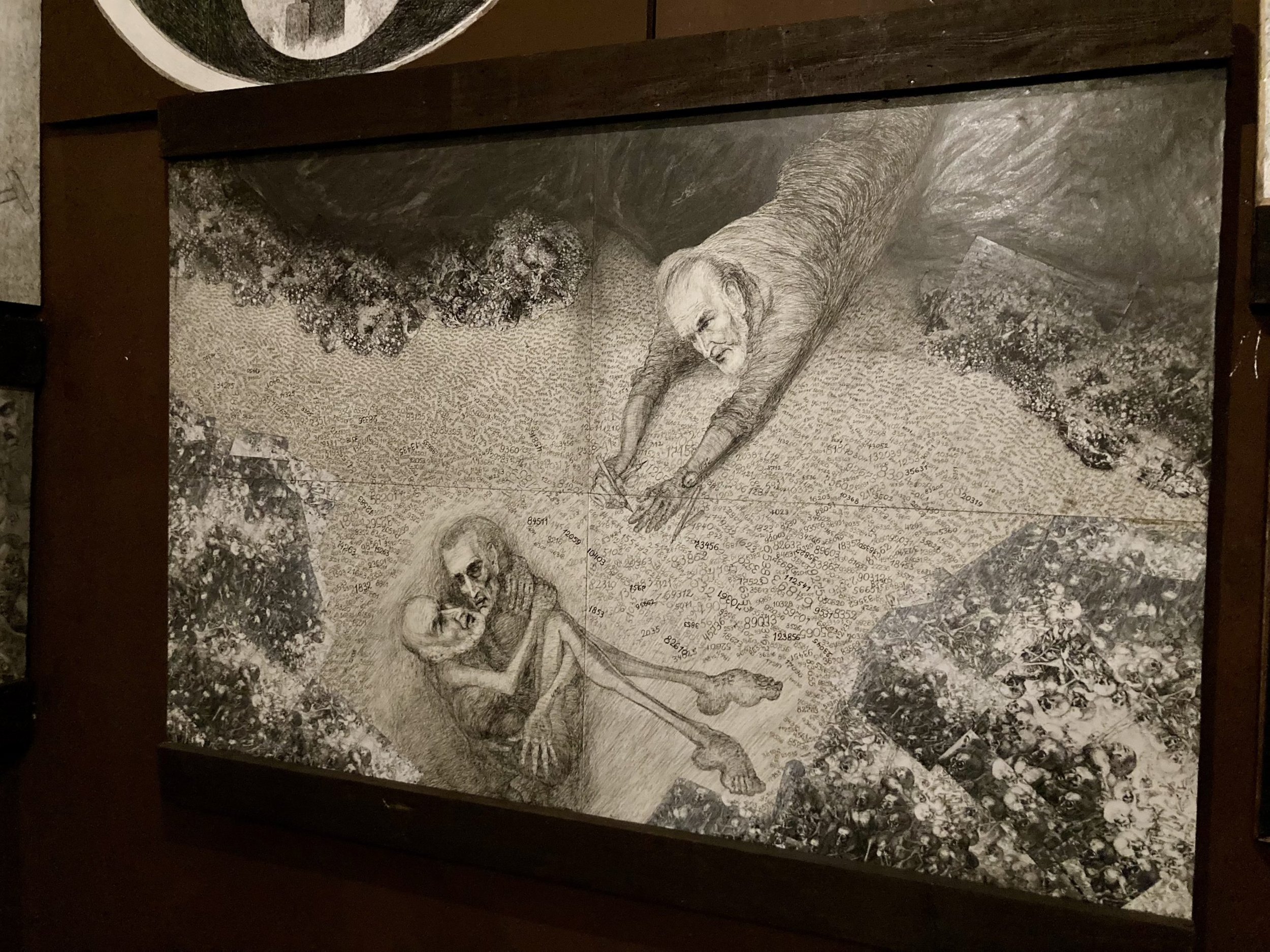

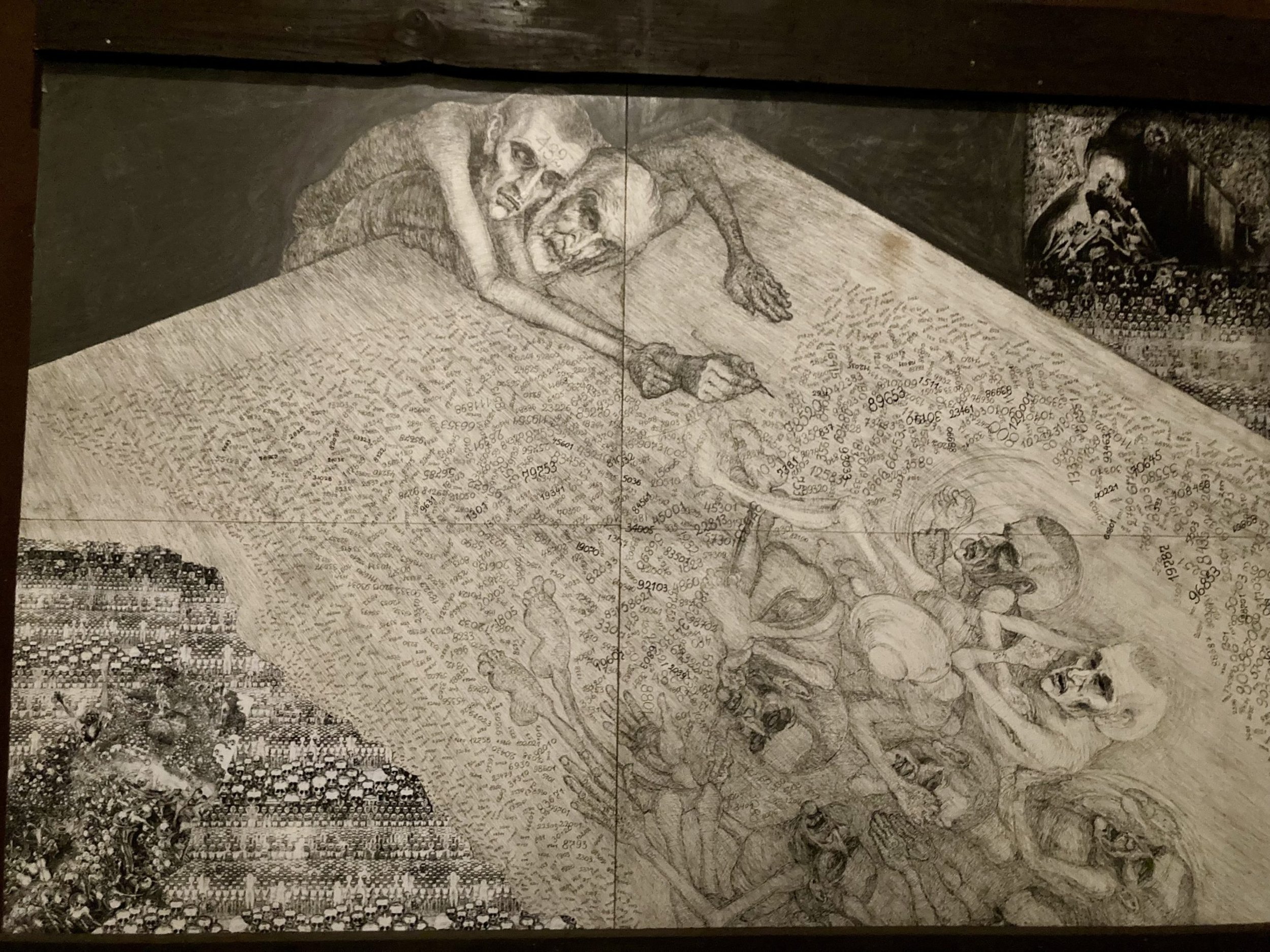

How Marian’s drawings still wander through my mind and heart, skeletal figures and eerie, hungry, broken, undignified eyes haunting me, skeletons barely breathing, barely standing, eating their deceased fellows, omnipresent scales pointing to the grave injustices, fat tyrants abusing and dehumanising in a never-ending spiral into more and more violence, death and horror.

I understand the silence now.

I understand the silence now and I feel horrible for having tried to push people beyond it.

Having been allowed to look through the eyes of Marian, see and witness his memories and experiences at the camp, allowed a deeper sense of understanding of the silence. The deep silence.

Thank you, Marian Kolodziej, inmate 432, for surviving hell for 5 years, for surviving the death march to Mauthausen, for surviving until you were able to release the memories onto paper. Thank you for your testimony.

The films they made us watch. The images they showed us when we had vowed to keep our eyes open yet longed to no longer see.

Human bodies, human souls abused far into their death, bulldozed into mass graves, broken, dehumanized skeletal figures rolling over, arms and heads twisting and turning to stare at you with broken eyes and an incredulous stare - how could you allow this to happen?

Children lined up inside a fenced off place, soldiers preparing the former Ambulanz car to be used as a killing device, a ferocious dog breaking the silence before the children are ushered into the carbon-monoxide filled car. No words spoken - does this terror need words?

The times when shooting individuals became too inefficient and thriving souls were ushered in large groups into gas chambers instead, their bodies to be burned in crematoria, later also in the open air when crematoria grew insufficiently small and the dead were piling high.

Or the silent witnesses, ordinary people who helped bury the dead - who were they? What did they know about what happened? Were they Nazis or silent, hidden protestors? How was it to know - and yet not know? How was it to live through the subtle and gradual process of dehumanisation that allowed them to be more and more brutal, reducing humans to numbers that don’t have a right to life?

The stories of the Sonderkommando, inmates given specific more prestigious roles, like pulling their dead fellows out of the gas chambers and carting them to the crematoria.

The moment when one Sonderkommando inmate recognised his mother in the group heading into the gas chamber. Knowing what would happen, he gave up his position and went with her. Reunited in death.

Or the Scheißkommando, the best job in camp, cleaning the latrines with bare hands and no water or soap to wash them afterwards, yet indoors, and a chance for black market exchanges and better survival. The best job in camp. Cleaning toilets with bare hands. The best job.

The red children's shoe, the thousands of glasses, the canes and braces, the hair. And how the Nazis sent all this back to Germany to be remade into other materials. Fancy fabrics from Jewish hair?

The book of names. The overpoweringly huge book of names. Filling an entire room, from wall to wall, one metre high, carefully inscribed with all the many names of the dead.

The execution wall, the orchestra, sadistic tricks, sadistic sarcasm, the many traps for the walking dead to be beaten, tortured, killed.

The sauna, the place of dehumanisation, losing first clothing and possessions, then names and hair, retaining merely a number tattooed into the forearm and some thin pyjama-like uniform.

The children’s barack, a place of great gloom and despair, where singing lullabies and sharing goodnight stories cracks your heart in two.

Unable to stay or leave I knew I would have to return - on my birthday to celebrate with them and sing for them once again. It’s the only thing that makes sense. Allowing them some joy and to be a child again for once - or maybe not even ‘again’ but just ‘for once’...

The soup at the fence - our lunch given to us daily by warm, loving hands. And how we could just stand on the outside and look in, warm up and feed ourselves, and think of the stories of soldiers throwing soup, mere water with a few rotten vegetables, through the fence onto the ground for the prisoners to lick off the earth and mud in their starving desperation.

The many hugs, the many tears, the constant nausea, the constant discomfort and pain in the body, the many motions and upheavals inside, the full spectrum of human emotions and experience.

Can I love the Germans? Can I love myself for being German? Can I own and honour my heritage and take accountability for all that comes with it? Can I stop othering and marginalising parts of myself?

Identity crisis.

The fact that we were just able to walk in and walk out and walk in and walk out. Unharmed. Unchecked. Alive, nourished, breathing, free.

And so we were - alive, free, willing to see, willing to be present and conscious to all the horror and pain and shame and guilt, willing to bear witness and remember the atrocities and remember the ones who were forced to live and die in such horrendous ways.

A group of powerful, strong souls, such pure presences, willing to shine their lights into this darkness, willing to sit in the fire of discomfort and bear witness.

The power of Hebrew. The incredible power and healing of Hebrew and Jewish ritual in a place that tried to eradicate it. The power of ritual and meditation and witnessing. Especially in a place like this - in the sauna, in the barracks, by the gas chambers and crematoria and the ash-pond. The power of a Jewish service inside the place where Jews had lost their identity, names, belongings, clothing, hair… A rectifying, reconciling, redeeming act of justice and dignity.

The incredible feeling of panic and life threat when stepping off the path between the trees, as if I could still be shot and killed at any moment.

The cold and the rain, the wind and the sun. The rainbows, the incredibly intense autumn colours, and all the sounds of this place.

Pondering how love can spring up in such crazy ways and places, and how many love stories there might have also been in Auschwitz, and how all the lost souls would want us to live, to love, to celebrate and enjoy life.

Little glimpses of humanity in this horrendously inhumane place. The priest sacrificing his life for a death-sentenced father, or the inmates and their strong sense of justice in this ocean of injustice.

Remember the scales!

Weigh your actions carefully! Weigh your actions carefully, they might harm someone.

I thought the dead would be haunting. I thought the souls would be scary.

They’re not. They’re incredibly welcoming and grateful that we are coming - and staying and being present. They have lessons for us. They have messages for us.

If you are willing to hear them and grief them, they are incredibly kind, loving and supportive, respectful.

The souls are waiting to welcome you, not haunt you.

It was very hard to be in Birkenau in the sunshine - as if the sun made the place even harder to bear.

From the moment we entered on day 3, the energy was particularly painful and hard to bear.

And then inside the children’s barracks, absolutely unbearable.

The darkness and weight is dense and intense. It’s hard to lift the darkness in a place like this.

So much. So many stories and inputs.

Too many horrendous stories.

And yet I also feel I can just let it all dissolve and do not need to hold any idea or form of ‘me’ together but can just let it all dissolve and merge and see what happens. Even though merging with the field and the land here is painful and overwhelming also.

I sometimes wonder why I feel so shit, nauseous, overwhelmed, in pain and tears - and then I remember again. I am in a place where 1.5 million people were murdered. No wonder. Why should I feel any different? Why should I feel any better?

I am allowing the horror to drop to deeper levels - this is what I wanted, to get away from merely intellectual immersion, and yet I also long to breathe freely, without the darkness trying to submerge and engulf me and take me over immediately.

How the wind stirs the dead. And how it makes this place even more eerie and creepy and spooky and horrible.

This place with all its facets.

And how haunting and painful and sad the barracks are at night.

And David’s song - his voice from one side, my voice from the other side, weaving a web of healing.

My birthday.

32.

A name that Li read was killed on her 32nd birthday. The Jewish service in the ruins of barrack 32. 32 in Hebrew - the heart.

Entering the year of the heart.

Meditated again on the landing platform, with endless circles of souls around me, around us. The Kaddish ceremony, the big memorial walk, the lunchtime pilgrimage to the children’s barracks to light a candle, be silent, sing, cry, share this moment.

The most beautiful gifts - my life, another year, a sacred blessing outside the ‘Stube’, a beautiful bracelet, a talisman and so much more.

The Shabbat service, the celebratory dinner, Mikko’s hilarious stand-up show with Bob, Patrick and Maciej, my birthday celebration on stage, and long hours of song.

Celebrating the renewal of life in a place that brought so much death.

Liminal experiences.

Loving impermanence.

Not knowing. Bearing witness. Loving action.

I choose to break the silence. I choose to remember. I choose to see and not close my eyes. I choose to stand up and act.

With deepest gratitude and love to everyone, and especially to David, Koho, Li, Markus, Kemp, Suzannah, Eliza and Sandra.

Thank you to Mikko and Asia for the beautiful pictures.